Nadja-Christina Schneider

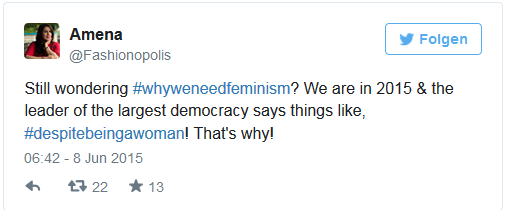

„Mahila hone ke baujud bhi“ – im Englischen mit „despite being a woman“ übersetzt – dieser selbstentlarvende Einschub in einer Rede, die der indische Premierminister Narendra Modi (BJP) Anfang Juni in Dhaka im Rahmen seines Staatsbesuchs in Bangladesch gehalten hat, sorgt seither für angeregte Diskussionen in der indischen Medienöffentlichkeit. Eigentlich wollte Modi darin das entschlossene Vorgehen von Premierministerin Sheikh Hasina im sog. Kampf gegen den Terror anerkennend hervorheben. Dies misslang ihm jedoch gründlich, denn eine unverändert patriarchale Haltung und unzeitgemäße Geschlechterstereotype sind nun die beiden ersten Assoziationen, die mit seinem denkwürdigen Auftritt in Dhaka in Verbindung gebracht werden. Unter dem Hashtag #despitebeingawoman postet seither eine stetig wachsende Zahl an Twitter-Userinnen und -usern ihre Kommentare und zahllosen Beispiele herausragender Leistungen und Errungenschaften von Frauen in Indien, aber auch satirische Inhalte und Karikaturen:

Bei der Vorstellung seines Kabinetts im vergangenen Jahr wurde der neu gewählte Premierminister teilweise noch überschwänglich von den Medien dafür gelobt, dass sich der Frauenanteil darin auf fast fünfzehn Prozent erhöht hatte und ein Viertel der Ministerposten mit Frauen besetzt worden waren. Die hindunationalistische indische Volkspartei (BJP) hatte sich generell aus wahlstrategischen Gründen in den vergangenen Jahren eine Rhetorik der Geschlechtergerechtigkeit zu eigen gemacht und vor allem im Wahlkampf 2014 eingesetzt. Insbesondere die säkular begründete indische Frauenbewegung beobachtet dies mit großem Unbehagen, denn zahlreiche Äußerungen und Handlungen von BJP-Mitgliedern sowie von anderen hindunationalistischen Organisationen im Umfeld der Partei sind nach wie vor kaum mit einem egalitären, liberalen Feminismus in Einklang zu bringen. Folglich bot Modi vielen, die an seinem überzeugten Engagement für eine gerechtere Geschlechterordnung in Indien stets gezweifelt haben, mit seiner Äußerung geradezu eine Steilvorlage, um seine patriarchale Haltung zu kritisieren und ihn mit Spott zu bedenken.

Twitter ist jedoch auch ein Medium, das Premierminister Modi selbst äußerst erfolgreich für seine strategische Kommunikation mit fast 13 Millionen Followern nutzt und so ließ die Gegen-Hashtag-Kampagne #ModiEmpowersWomen ebenfalls nicht lange auf sich warten. Viele englischsprachige Medien weltweit scheinen dennoch ausschließlich über den Hashtag #despitebeingawoman zu berichten, der vielfach als „social media storm“ bezeichnet wird, den Modi durch seine Äußerung entfacht habe.

Diese Skandalisierung und die wachsende Zahl an Berichten von Medien über das, was sich in den sozialen Medien tut, sagen auf der einen Seite viel aus über die rapide gewandelten Medienumgebungen und kommunikativen Dynamiken in der indischen Gesellschaft. Auf der anderen Seite lässt die starke Medienresonanz auf Modis Äußerung aber auch die Zentralität von genderbezogenen Themen in dieser gewandelten indischen Medienlandschaft erahnen. Es ist zwar keinesfalls neu ist, dass die Situation von Frauen, Diskussionen über Frauenrechte und Gleichberechtigung oder genderbezogene Diskriminierung ein sehr großes Interesse der indischen Medien und generell in öffentlichen Debatten allgemein erfahren, doch die Medienberichterstattung und daran anknüpfende Anschlusskommunikation hat sich zweifellos im Zuge der fortdauernden Debatte über sexuelle Gewalt seit 2012 stark verdichtet.

Nadja-Christina Schneider, Ringvorlesung Kultur und Identität am Institut für Asien- und Afrikawissenschaften der HU Berlin, 16. Juni 2015

[to loiter: herumbummeln, herumhängen, rumlungern]

Dass Frauen durch das vermeintlich zweckfreie „Herumlungern“ im öffentlichen Raum ihre Sichtbarkeit und Rechte als Bürgerinnen geltend machen können, ist die zentrale Idee des Essays „Why loiter? Radical possibilities for gendered dissent“ von Shilpa Phadke, Shilpa Ranade und Sameera Khan. Der Text erschien bereits 2009, also drei Jahre vor dem sog. Delhi Gang Rape Case, der die indische Öffentlichkeit aufwühlte und zu einer bis heute andauernden Debatte über die Sicherheit und Mobilität von Frauen im öffentlichen Raum geführt hat. Insbesondere vor dem Hintergrund der häufig vertretenen Ansicht, dass Frauen im Interesse ihrer eigenen Sicherheit ihre Mobilität möglichst einschränken sollten, wird „Why loiter?“ von jungen Frauen und Männern in Indien als Manifest und Aufforderung zur Handlung gelesen und multimedial umgesetzt.

Am Beispiel dieses Textes und seiner Wirkungsgeschichte gab der Vortrag von Nadja-Christina Schneider einen Einblick in den aktuellen Diskurs über „Gefahren“ für und „Sicherheit“ von Frauen im urbanen öffentlichen Raum in Indien. Der Vortrag wurde am 16. Juni 2015 im Rahmen der Ringvorlesung Kultur und Identität am Institut für Asien- und Afrikawissenschaften der HU Berlin gehalten.

Talk by Jamila Adeli, Internationales Künstlerhaus Büchsenhausen, Innsbruck, Austria, May 2015

Photo credit: Jamila Adeli, Installation shot at Pepper House, Kochi-Muziris Biennale, India

The contemporary art world appears to be quite a utopian – as in ideal – place: no more nation-state borders, no more identity issues, and no more language problems. Artists, curators, artworks, texts and audiences seem to flow with ease through different cultural fields. And the ongoing expansion of biennials and art fairs give the impression of a truly global map of contemporary art.

When critically thinking about these global flows and how they compose a global map of art, we unquestionably need to look a considerable bit deeper. The contemporary art world is not a product of flat trajectories of globalization – as it is often alto hastily assumed. It is a complex social space, which is in the process of becoming translocal. At the example of the practice of contemporary curating, I aim to “ground” these global flows and to identify how they encounter in order to make sense of what “being translocal” could mean for the contemporary art world.

My presentation introduces and combines two types of interfaces, which are linked through their most distinguished characteristic: a practice that constructs meaning at specific locations where global flows of the contemporary art worlds intersect.

Curating produces meaning through the accompanied production, selection and juxtaposition of artworks or artistic movements in order to demonstrate specific moments or phenomena in time. It also developed into a practical and academic tool to analyze historical and contemporary artistic practice, to create order and new perspectives within the aesthetic matters.

Photo credit: Jamila Adeli, advertisement of Kochi-Muziris Biennale in Creative Brands Magazine

Biennials, on the other hand, are large-scale exhibitions, which are held to visualize and discuss the present state of contemporary fine art. Since Biennials are hosted in a city that had encounters with global flows, they are a true interface: contact zones of „local“ and „global“, of „center“ and „semi-periphery“, of institutional art theory concepts and day to day cultural life. They are not only interfaces of global art flows but also form hubs within a network of cultural urban centers. A Biennial certainly places a city, region or nation on the global map of art (Charlotte Bydler), and they are important meeting points for local and international artists, curators, critics and audiences.

The presentation exemplifies its main arguments at India’s recent Kochi-Muziris Biennale. Inaugurated only in 2012 by the Government of Kerala and the two artists, Bose Krichnamachari and Riyas Komu, the Kochi-Muziris Biennale is already being considered as the new Biennial format of the 21st century – not only from the specific local viewpoint of India: both editions were perceived as a truly translocal experience of contemporary culture, and hence an experience that highlights not only decisive localization processes but also how such processes connect to global flows of knowledge and aesthetics.

Gastvortrag von Nina Khan am Institut für Indologie und Zentralasienwissenschaften der Universität Leipzig, 05.05.2015

Der Vortrag führte zunächst in das Forschungsfeld der „Neuen Geber“ in der Entwicklungszusammenarbeit (EZ) ein und zeichnete aktuelle Entwicklungen und Debatten nach. Dabei wurde der langsame Umbruch der globalen Entwicklungshilfearchitektur – laut Woods (2008) eine „stille Revolution“ – skizziert und dessen Bedeutung nicht nur für strukturelle Veränderungen (wie z.B. die Diversifizierung der Geberlandschaft und die daraus resultierende größere Wahlmöglichkeit und stärkere Position der Nehmer) sondern auch für eine normative Pluralisierung der EZ konstatiert, die sich in Entwicklungsdiskursen wiederspiegelt.

Der Vortrag führte zunächst in das Forschungsfeld der „Neuen Geber“ in der Entwicklungszusammenarbeit (EZ) ein und zeichnete aktuelle Entwicklungen und Debatten nach. Dabei wurde der langsame Umbruch der globalen Entwicklungshilfearchitektur – laut Woods (2008) eine „stille Revolution“ – skizziert und dessen Bedeutung nicht nur für strukturelle Veränderungen (wie z.B. die Diversifizierung der Geberlandschaft und die daraus resultierende größere Wahlmöglichkeit und stärkere Position der Nehmer) sondern auch für eine normative Pluralisierung der EZ konstatiert, die sich in Entwicklungsdiskursen wiederspiegelt.

Drei Grundannahmen bildeten den Hintergrund der folgenden Diskussion aktueller Kernthemen des staatlichen indischen Entwicklungsdiskurses. Erstens, dass die Beziehungen der Nord-Süd-EZ nach wie vor von asymmetrischen, rassifizierten Machtbeziehungen gekennzeichnet sind, die durch Entwicklungsdiskurse gestützt werden. Zweitens, dass der Neue Geber Indien als ehemals kolonisiertes und weiterhin Empfängerland, das als solches lange Zeit als „unterentwickelt“ und „rückständig“ kategorisiert wurde, nicht dieselbe Entwicklungsrhetorik der traditionellen Geber des Globalen Nordens verwenden wird. Drittens, dass alternative, eventuell gleichberechtigtere Entwicklungsdiskurse einen Einfluss auf die Machtbeziehungen in der EZ haben können.

Nach einer Einführung in die Geschichte, Struktur und den Umfang indischer EZ erfolgte ein Einblick in eine exemplarische Analyse des staatlichen indischen Entwicklungsdiskurses. Diese ergab mehrere wiederkehrende Themen, die anhand von Zitaten aus Artikeln des Indischen Außenministeriums, Aussagen indischer Politiker_innen sowie Webseiten und Publikationen staatlicher Entwicklungsprogramme veranschaulicht wurden. Kernthemen sind dabei Reziprozität, die Abgrenzung von traditionellen Gebern sowie Geber-Nehmer-Beziehungen, die Betonung einer Entwicklungspartnerschaft und der eigenen Erfahrungen als „Entwicklungsland“, eine geteilte Kolonialgeschichte sowie eine propagierte Süd-Süd-Solidarität.

Abschließend aufgeworfene Fragen beinhalteten die Kongruenz von staatlicher Rhetorik und EZ-Praxis, das Potential alternativer Diskurse für diskursive Verschiebungen im globalen Kontext, eventuell abweichende Diskursstränge je nach Nehmerland bzw. –Region und die Auswirkungen diskursiver Verschiebungen auf die tatsächlichen Machtbeziehungen in der EZ.

Max Arne Kramer

Am 22.04.2015 fand in den Räumen der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin eine von Dr. Sanaa Alimia und der Berlin Graduate School Muslim Cultures and Societies (BGSMCS) gemeinsam organisierte Filmvorstellung zum Kaschmirkonflikt statt. Der Film „Bring Him Back“ (2015) behandelt den politischen Einsatz von Shamli Begum, der Mutter des 1984 in Indien gehängten kaschmirischen Seperatistenführers Maqbool Bhat. Seit über dreißig Jahre kämpft sie für die Rückführung des Leichnams ihres Sohns in das leer stehende Grab auf dem Märtyrerfriedhof Srinagars, der Sommerhauptstadt des indisch-verwalteten Teil des umstrittenen Gebiets. Die Zuschauer wurden durch Fahad Shahs Film mit der biopolitischen Dimension des Kaschmirkonflikts konfrontiert: er zeigt, wie nicht nur der Mobilität der Lebenden in einem militärisch besetzten Land enge Grenzen gesetzt sind, sondern auch, dass durch die Bewegung eines Leichnams aus der Sicht staatlicher Entscheidungsträger unkontrollierbare politische Passionen unter der Bevölkerung ‚entflammen‘ könnte. Es folgte eine Diskussion mit dem Filmemacher und Medienschaffenden Fahad Shah, Herausgeber des bekannten kaschmirischen Online-Journals „The Kashmir Walla„. Shah betonte die Notwendigkeit für die kaschmirische Jugend, auf allen Ebenen des medialen und kulturellen Ausdrucks aktiv zu werden. Sein Film, so Shah, sei eine wichtige Ressource der Erinnerungspolitk seiner Generation, der sich immer mehr Kashmiris bedienen, um „die orientalistischen Bilder des indischen Kolonialismus anzufechten“.

Eine neuere Publikation von Shah „Of Occupation and Resistance“ präsentiert Essays vorwiegend junger Kashmiris aus der Generation der ‚Kashmiri Intifada‘ (ab 2010), die ihre Erinnerungen an die Kindheit in einem Konfliktgebiet durch verschiedene Formen zum Ausdruck bringen.

Alexa Altmann

An ad recently published in The Hindu for the luxury brand Kalyan Jewellers has sparked a controversy over colonialism, racism, child-labour and slave-fantasies as well as over public image projection and accountability. The depiction of movie-star Aishwarya Rai Bachchan in the fashion of a European colonial-era aristocrat, bejeweled, poised and shaded from the sun by an undernourished black child-slave, has prompted the outrage of several feminist and child rights activists as expressed in an open letter to Rai Bachchan and Kalyan Jewellers. The authors equally draw attention to the racist implications of the slave fantasy depicted in the advertisement by referencing the colonial heritage of comparable historic portraitures and to the romanticisation of child servitude. While Kalyan Jewellers promptly issued an apology and withdrew the image, Rai Bachchan’s publicist declared the final layout featuring the black child-slave was edited without the actress’ knowledge and consent and thus only the responsibility of the brand’s creative team. The activists countered by questioning this statement and Rai Bachchan’s alleged lack of control over her own public image. They demand Rai Bachchan to take a clear stand, both as an icon and in her role as UN Ambassador, against racism and the trivialization of servitude as well as take full responsibility for the commercialization of her public image projection.

Mette Gabler

Recently, a video has gone viral again. This time it is caught in a triangle of consumerism, gender and change, and set off a debate on feminism, gender equality, class and empowerment. The advertisement “My Choice” selling the magazine and brand Vogue as well as the idea of empowerment was produced as a collaboration between director Homi Adajania and Indian actor Deepika Padukone. This advertisement is part of the social awareness initiative of Vogue India, #VogueEmpower. Deepika Padukone’s voice carries the message, based on a piece written by Indian screenwriter Kersi Khambatta, and begins with the words “My body, my mind, my choice”. The black-and-white film cuts between images of female faces and bodies of 99 people of different ages, religions and belonging, including film critics, directors, and other figures of the so-called ‘glamour’ industry, as well as Deepika Padukone herself. The lines address a wide range of topics relevant in feminist discourses, from body image, gender norms, sexuality, and reproductive rights, as well as love, romance and relationships. It ends with the statement “Vogue Empower. It starts with you”, which reflects the aim of the advertisement, to “encourage people to think, talk and act in ways big or small on issues pertaining to women’s empowerment. The message is simple: It starts with you” given on Vogue’s YouTube channel alongside the video.

The intentions, content and implementation of the message are currently discussed on social media and in various forms of national and international online press. Voices include private individuals, activists, journalists, representatives of right wing politics, and film celebrities.

Vogue Empower seems to convey the idea that it is up to each individual to engage, get involved on their own account but potentially also beyond, because it might “start with you” but where does it go after that? The understanding of empowerment, in particular, is now under grave scrutiny and criticised in various ways. The debate ranges from the question which ideas are valuable to address to what empowerment can be, and if this form can at all be a vehicle for empowerment. Deepika Padukone’s own perspective on empowerment is shared on Vogue’s YouTube Channel: “I’ve always been allowed to be who I want to be. When you’re not caged, when you don’t succumb to expectation, that’s when you’re empowered.”

Although some have supported the messages and see it as a celebration of women “not in a way that society expects them to be but in way of her being an individual, a separate entity, one who can make choices of her own and live life on her own terms.” (http://www.scoopwhoop.com/inothernews/celebrating-women/) and being truly feminist (http://www.thehindu.com/trending/deepika-padukone-in-my-choice-video-of-vogue/article7056615.ece), the debates that followed strongly questioned whether empowerment conveyed in the video was relevant or useful.

Several strands of critical voices point out that the issues addressed in the video only target a privileged minority of the population in India. Accordingly, the issues of clothing, bodily integrity and authority are a matter of personal choice and therefore would not qualify as topics of female empowerment (/http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/entertainment/hindi/bollywood/MyChoice-Twitterati-cheer-for-Deepika/photostory/46753891.cms). This critique seems to create a division between one group of people, privileged and not in need of empowerment and another underprivileged group, who benefit from empowerment. The juxtaposition of personal choices is in many articles posed against issues of public concern such as female foeticide, abuse, access to education, domestic violence, rape, harassment at workplace, equal leadership opportunities, the pay gap, financial independence, the intrusive male gaze, and everyday sexism (http://www.thehindu.com/opinion/op-ed/wanted-less-style-more-substance/article7058383.ece). In this I see a certain hierarchical setup between issues that according to these critiques are worth addressing and issues that can be dismissed as privileged luxury problems.

Some of the critical stances seem to contradict each other. One on side, the dilemma of potential dangers or repercussions as unwanted consequences of the choices made beyond what is expected and set as the norm is considered. On the other side, this campaign is regarded for its potential harm is could do to the existing feminist movements. It is seen as a appropriating of women’s rights movements and branding feminism into a slick, cool and glamorous package instead of acknowledging the hard work that goes into it. In my opinion, one kind of struggle for feminist ideals is thereby romanticised while the other is thought of as easy. While surely the activism and work done in the history of women’s movements has not only been important but also dangerous and full of hardship, making the choices addressed in the video could also be a source of struggle.

Some articles debate the messages itself as hypocritical, in more than one way. According to this point of view, the choices “sold” in this ad stem from an industry riddled with stereotypical definitions of beauty and femininity thereby only supporting one kind of choice and freedom, one that fits within the frame of these definitions. Moreover, some saw the video as sexist in that the same demands of freedom to choose sexual partners “outside of marriage”, which was by many read as promotion of adultery, bigamy, and indifference, could not be claimed by the male part of the population. All these viewpoints illustrate that the video has definitely created a debate with diverse perspectives.

The debates continues to also inspire creative media output. While for example Amul, an Indian dairy cooperative based in Gujarat known for commenting on current popular, political, social and cultural events, incorporated the debate in its campaigning, by focusing on the divided opinions, others created responses delivering their own point of view: several examples of a male version of “My Choice” (here is one arguing that the Vogue ad is sexist : http://www.ndtv.com/offbeat/beer-belly-is-my-choice-spoof-of-deepika-padukones-vogue-video-751043), a dog version, and other spoofs e.g. incorporating the images of the “My Choice” video into other advertisements to highlight the sales of products over the social message (http://indianexpress.com/article/lifestyle/feelings/can-you-spot-the-hidden-ads-in-deepikas-mychoice-video/).

The reactions to the video must be said to be as diverse as the potential audiences, as the people voicing the critiques and reacting to the messages are all part of the audience (for another text on the critical viewpoints visit: http://kafila.org/2015/04/09/being-empowered-the-vogue-way-is-there-anything-left-to-be-said/). Each view contributes opinions, setting up a debate and potentially creates new perspectives in the feminist movement on gender equality, and what empowerment should mean. In light of this, the campaign has definitely proved successful in the goal to “encourage people to think, talk and act in ways big or small on issues pertaining to women’s empowerment”.

And I wonder, is being critical not also a sign of being privileged? There is a certain literacy that comes with the possibility of being part of the audience, first of all accessibility but also usage of a technical devices with a screen. Second, to be able to react to the issues mentioned in the short film one must not only understand the English language but also have an idea or understanding of empowerment as a concept, as well as being versed in debates on gender and the women’s rights movements. While for many the message of the “My Choice” advertisement is selling both a product and an idea, catering to a small group of people, is it not a crass assumption, that no one can be inspired by it in other ways than simply disagreeing? Sparking creativity beyond finding what is wrong with it, but potentially how it is relevant to some, affecting some part of their realities, or by simply inspiring some to get more information, and challenging some norms and expectations? Because, in the end, why is it a question of either or? And not a statement of all, everywhere, all the time? If the voices in reaction to this advertisement are diverse, why not also the possible impact? Debate being the source of movement and change.

See also: transgender-version of ‚My Choice‘

Film celebrates 50 years of Satyajit Ray’s sleuth

Perhaps few other characters in Bengali fiction stir as much feelings in the young and the old alike as Feluda, the detective personality created by Satyajit Ray. Feluda who came to life through a story in a children’s magazine in 1965, ‘turns’ 50 this year. A documentary tells his story. Text: Indrani Dutta/Suvojit Bagchi

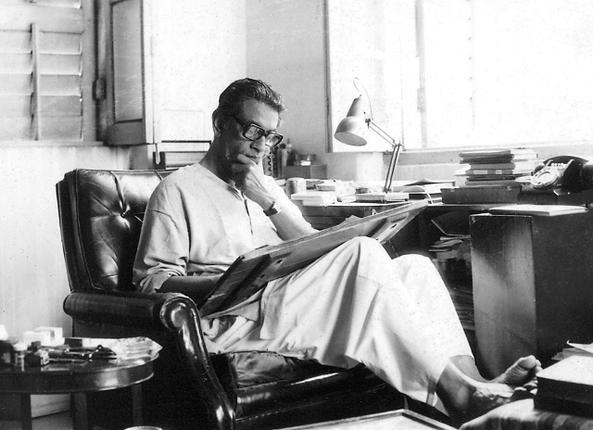

The first short story of Feluda, with sketches by Ray was published in 1965-66 in Sandesh, a children’s magazine. The maiden Feluda novella titled ’Badshahi Angti’ (The Emperor’s Ring) with more sketches by Ray appeared the same year. The magazine was launched in 1913 by Ray’s grandfather– writer, painter, printer Upendrakishore Raychowdhury. The editor’s mantle was donned later by Ray’s father, poet, illustrator and playwright, Sukumar Ray. (Courtesy: Ray Society)(Source: The Hindu, April 18)

Reader comment by Koel (The Hindu, April 20):

“Feluda – irreplaceable. I think he is the greatest tribute to the literary and intellectual middle class Bengali psyche”.

Writer and auteur, Satyajit Ray, created many of his characters sitting in this chair in central Kolkata’s Bishop Lefroy Road. One of his char-acters, Feluda, the quintessential Bengali gentleman sleuth, is com-pleting his golden jubilee later this year. (Courtesy: Ray Socie-ty)(Source: The Hindu, April 18)

Den vollständigen Artikel finden Sie auf thehindu.com

SCROLL.IN, 14 March, 2015

Mayank Jain

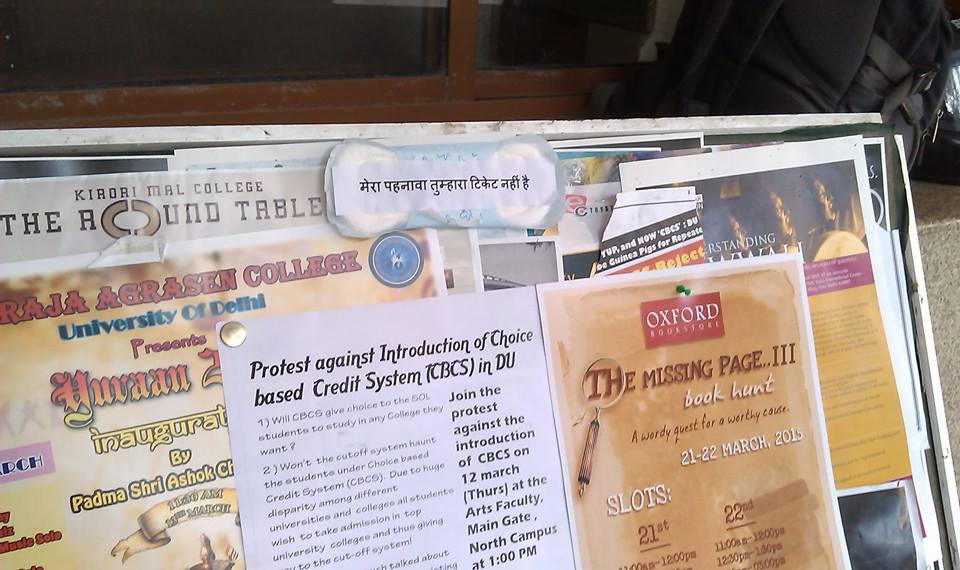

Inspired by a German artist, students of the University of Delhi and Jamia Millia Islamia are displaying feminist messages on sanitary napkins.

Sanitary napkin sales have been shooting up around colleges in Delhi, thanks to a public art project inspired by German artist Elone. On International Women’s Day on March 8, Elone scribbled feminist messages on sanitary pads and put them up all over Karlsruhe city. Students of various colleges in Delhi have taken up the challenge, and have covered campus walls and trees with statements on gender equality.

An image from Elone’s campaign.

Students of the Jamia Millia Islamia university made the first move on March 12. “We were really impressed with what happened in Germany and decided to do the same thing on our campus,” said a student activist on the condition of anonymity. The campaign hopes to bust taboos about menstruation and target the larger culture of misogyny. The messages include ‘Streets of Delhi belong to women too’, ‘Rapists rape people, not outfits’, and ‘Period blood is not impure, your thoughts are’.

“It’s not just students ‒ educated people, including teachers, tend to view menstruation as something unnatural and despicable,” the activist said. “We want to send a message that sexism cannot and will not be tolerated.”

Easier said than done. Jamia officials took down the pads, which were put up by the students without permission. The students are undeterred, and took the campaign outside the campus and onto the streets of Delhi. “We expected some opposition but this was a shock,” said another student, who had spent a whole day putting up the pads, on the condition of anonymity. “We are going to take the message forward to the city until the hostility ends.”

Meanwhile on Friday, a group of students from the University of Delhi showed their solidarity by putting up similar revolutionary pads across the North Campus area. “We simply want people to understand that menstruation is not a crime and a girl should not be victimised for something so natural,” said Rafiul Alom Rahman, who initiated the campaign at DU. “We put feminist messages on the pads even though we knew that people will not be okay with seeing sanitary pads with red paint.”

DU officials, and possibly some students, also did not approve of the campaign. Some of the pads were found to be torn, while others were pulled off trees. “A security guard pulled a pad out of his pocket and asked me to put it somewhere else,” Rahman said. “We are not going to be cowed down. We are thinking of ways to make this campaign even bigger and involve other universities and students.”

Here are some photographs of the public art campaign from social media.

Read more at: Why are sanitary pads with little notes stuck on trees and walls of Delhi colleges?

You’re a ‘bad girl’ if you fight rapists or go out with boys: New Meme

You’re a ‘bad girl’ if you fight rapists or go out with boys: New Meme

By: Meghna Malik, The Indian Express

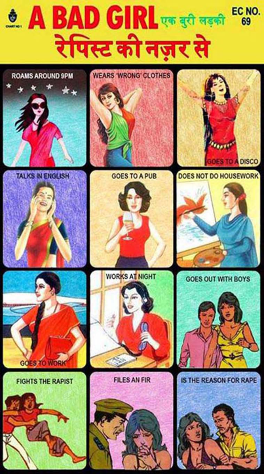

Barely a month after the first ‘bad girl’ meme went viral on the internet, another ‘bad girl’ chart is doing the rounds on social media. The chart comes shortly after Leslee Udwin’s controversial documentary, ‘India’s Daughter’, which is based on the rape and murder of a 23-year-old student in December 2012. This documentary has been banned by the government of India.

Titled ‘Ek Buri Ladki – Rapist Ki Nazar se‘, this satirical chart shows 12 illustrations that depict the qualities of a bad girl, according to a rapist. Going by the chart, in the eyes of a rapist, a girl is a ‘bad girl’ if she roams around after 9 PM, fights the rapist or goes out with boys.

The chart further reads that a girl who talks in English, goes to a pub or files an FIR against the rapist is also a bad girl.

Quelle: http://indianexpress.com/article/trending/youre-a-bad-girl-if-you-fight-rapists-or-go-out-with-boys-new-meme/

Eine größere Version des Posters kann hier angesehen werden: bad-girl31